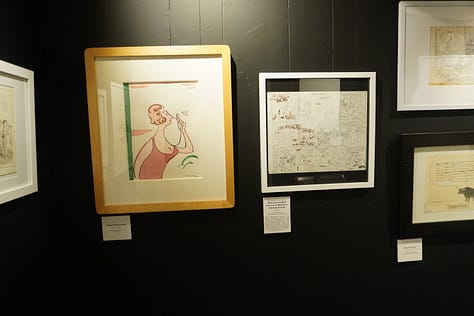

Below are some photos from the exhibition I curated to celebrate The New Yorker’s Centennial this year. Started over a year ago, It was a true labor of love. I reached out to collectors and artists, and gathered over 130 pieces, wonderful art that covers the last century with great humor, beauty and insight.

A chronological layout, I had to make a choice to have primarily only one drawing per artist. Sadly, I couldn’t include everyone, that would be a show three times as large. My choices included artists who contributed a large amount of work to the magazine over the years, and those who, while they may not be as prolific, nonetheless are signifcant in another way in terms of their contribution to the artistic conversation.

This conversation through cartoons has been a national dialogue, one I love to look at.

The copy I wrote for the wall of the exhibition at the Society of Illustrators is below. There is so much history here to share, but I will save that for another day. It is a wonderful museum, run by a wonderful staff who made this effort enjoyable. Yes, there were headaches and a major stumbling block that I won’t go into (not from the Society nor The New Yorker), but by and large it was a joy. The New Yorker supported me as an independent curator, for which I am grateful. And I could not have done this without the advice and friendship of my husband, cartoonist, collector and historian, Michael Maslin. We all had a lot of laughs in the process.

Drawn From The New Yorker: A Centennial Celebration

It was a bold idea, maybe crazy, but Harold Ross and Jane Grant had a notion to start a humor magazine for New Yorkers. Magazines were thriving in the 1920’s and they saw an opening for a witty, sophisticated comic weekly that would appeal to the youth of the Jazz Age. Together, they founded The New Yorker in 1925.

Ross, a Colorado native and former editor at Stars and Stripes and Judge Magazine, and Grant, a New York Times reporter, spent the year leading up to 1925 scheming and planning. They knew what they didn’t want, but it was unclear what this new magazine would look like; however, they did know that the unnamed publication would contain a lot of great art.

A key early move was to hire Rea Irvin, Art Editor for Life Magazine, who was respected and well established in New York. Creator of the magazine’s first cover image, the iconic Eustace Tilley, Irvin also adapted The New Yorker’s iconic font. He helped bring on board the best artists the city had to offer.

Struggling for readership in its first year, Ross and his team, including financial backer Raoul Fleishman, considered ending publication. While they were walking in midtown discussing The New Yorker’s fate, John Hanrahan, the magazine’s lawyer, said,

“I can’t blame Raoul for a moment for refusing to go on, but it’s like killing something that’s alive.”

The New Yorker went on to thrive beyond expectations.

The art was key to the magazine’s success. Not only were its covers beautifully designed and drawn, but the cartoons were unlike

anything seen before. Ross, Irvin and fiction editor Katharine White worked with the artists to refine the cartoons to what we now know as “the New Yorker cartoon.” Single panel cartoons had previously been illustrated jokes: a line of dialogue and a drawing to depict what was being said. At The New Yorker, the artists created cartoons that were a dance of word and line, seamlessly in step to deliver an idea. Ross asked his contributors to avoid “decorative” drawings and strive for what he called “idea drawings.” (To this day, they are called “drawings” in the table of contents.) Ross clarified:

“We want drawings which portray or satirize a situation, drawings which tell a story. We want to record what is going on, to put down metropolitan life and we want this record to be based on fact—plausible situations with authentic backgrounds.”

Eventually, the cartoons were so successful that he was heard to exclaim, “Get the words more like the art!” Ross and editors would spend an afternoon looking at submissions, debating their efficacy. Ross famously used a knitting needle to point to parts of cartoons, and was reported to have asked, “Where am I in this picture?!”

In the 100 years since its first issue, the art has been instrumental to The New Yorker’s success. From bold brushes to light lines, ink to charcoal, we witness creativity and humor at its best. The artists of The New Yorker have always had their pulse on culture and politics, often obliquely. They reflect what we are experiencing in our daily lives, they help us laugh. What could be a better way to understand ourselves?

Looking at the covers and cartoons, the viewer can’t help but see an individual behind the work. These pieces are expressions of the artist’s humor and world view. For the most part, the editors at the magazine let the artists do their magic and rarely commissioned the work. It is the reason why, as a young girl, I wanted to be a part. It was somehow clear to me in those pages I studied in the 1970’s that the editors were looking for voices, unique ways to express the world we live in: sometimes with humor, sometimes in all seriousness, sometimes both. As fate would have it, I am lucky to have been a contributor to The New Yorker since 1979, just shy of half the magazine’s life.

It is an honor to curate this show and to celebrate the incredible, beautiful voices of the artists of The New Yorker.

Thanks for being here, see you tomorrow!

Wow, what an undertaking. This is massive. But, as always, you did a sterling job, despite the challenges. I am going to try my darndest to get in to see it. Oh I love this "the artists created cartoons that were a dance of word and line." Beautiful and evocative. Well-done. We have the tome, The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker. It will be awesome to see some of these in the original in your exhibit

Humor is often in the eye of the beholder. Thank you Liza for sharing your eyes with us.