As I prepare for my virtual class tonight on the History of The New Yorker cartoon, I wanted to share something with you about artists and humor and “being true” to what it is you believe.

It comes from my own research for my book, Very Funny Ladies, a history of the women who drew and draw for the magazine. In the early days of The New Yorker, co-founder and editor, Harold Ross, sometimes communicated with artists in letters. In the New Yorker Archives at the NY Public Library, I found the following correspondance between Ross and Alice Harvey, an artist who had been with the magazine since 1925 (it was started that same year).

This exchange started out with a letter of frustration from Harvey, and in his response, one sees clearly Ross’ vision for the cartoons. I love Harvey’s powerful exchange with the head of the publication—a very confident woman who is clear on her own vision.

Dear Harold Ross, Do you know what your New Yorker boys are doing? Sending me an idea asking me to illustrate it… Then they say it’s lovely, but the idea is not fresh and new as it should be. So they withhold my check and tell me… Surely I don’t want them to pay for something they can’t print. Will I do, darn it! You all asked me to illustrate the idea I did it and did it well I can’t afford to indulge your editors in a lot of temperament. This sort of thing has happened to me before and it’s happening to other artists. most sincerely yours, Alice Harvey

Ross’ response, edited a tiny bit:

Dear Alice Ramsey,

Your letter brings up something which to my mind is 1000 times as important as a single drawing however, and it is this. I’ll begin at a the beginning.

For years and years before the New Yorker came into existence the humorous magazines of this country weren’t very funny or meritorious in any way. The reason was this: the editors bought jokes, or gags, or whatever you call them for five dollars or ten dollars and mail these out to the artist, the artist drew them up and mailed them back and were paid. The result was completely wooden art. The artist attitude towards a joke was exactly that of a short story illustrated towards a short story. They illustrated the joke and got their money for the drawing. Now, this practice led to all humorous drawings being “illustrations“ —it also resulted in there being wooden, run-of-the-mill products. The artist never thought for themselves, and never learn to think. They weren’t humorous artists, they were dull witted illustrators. A humorous artist is a creative person, an illustrator isn’t, at least they’re not creative so far is the idea is concerned, and in humor, the idea is the thing.

I judge from your letter, you apparently don’t realize that you are one of the three or four pathfinders in what is called the new school of American humor. Your stuff in Life before The New Yorker’s start might well be considered the first notes of that new humor. I remember seeing it and being encouraged by it when I was thinking of starting The New Yorker. It had a lot to do with convincing me that there was a new talent around for a magazine like this. And now you speak of “illustrating jokes!“ I always see red when an artist talks of illustrating a joke, because I know that a such a practice means the end of The New Yorker, the new school of humor and all. Unless an artist takes a hold of an idea, does more than “illustrate,” he, she is not going to make a humorous drawing. I haven’t any quarrel with any of your work to date in this respect. You still draw Alice Harvey drawings and God knows give something to them, but I’ve simply got to run on this way when I hear or see the word “illustrate” in connection with a joke.

Pardon me, for having written in such length , I got started and off I went, it seems. I’d like to talk to you about this, but how can you talk to to anyone who retires to Connecticut and is never seen around, which is what most of our contributors have done? Sincerely, HW Ross

She wrote him back, expressing pleasure at hearing from him, because “you had become nebulous to me , hearing of you only in such connections as ‘Mr. Ross doesn’t think this is funny’.” The difference, she wrote, “…comes down, like many discussions, to definition of terms. As a matter of fact, I hate always being humorous. What I like is being true— and knowing people, and getting a thrill out of them, and drawing it.”

She goes on:

It’s too bad it’s so hard to run a magazine but if you’re going to be so frightfully idealistic about it, you shouldn’t change captions and you shouldn’t ask artists to change their drawings. I think the letter you wrote me Harold Ross was awfully nice but full of bunk… I really don’t see what you or I or anybody else are going to do about anything… You’ve done something perfectly swell with The New Yorker, I hate to obstruct your vision in anyway. Thanks for bothering with me, after I did appreciate being explained to. I’ll cooperate. Best I can but you better not send back that picture. Sincerely, Alice Ramsey

My commentary in my book:

Ross operated his New Yorker less as a magazine then, as a kind of a great laboratory, we’re associates were courage to pursue individual projects get in that pursuit advanced a common cause… The editor encourage people to write or draw or what they wanted… Everyone else, himself included, was to be at their service. Besides his faith, Ross gave his people strength and the comfort knowledge that he would always be there for them. Add to this, Ross is intrinsic understanding. The writers an artist were different from other people must be treated– tolerated he was more likely harumph – as such. He believed that the same unique vantage point that made creative people insightful, could also render than vulnerable impractical and maddeningly unreliable.

“I think he thought that people with talent didn’t in general know enough to come out of the rain,” said William Maxwell, “and he was trying to hold an umbrella over them.”

Harvey’s words about “being true” resonate so much with me. It makes for the best stuff if you can do it.

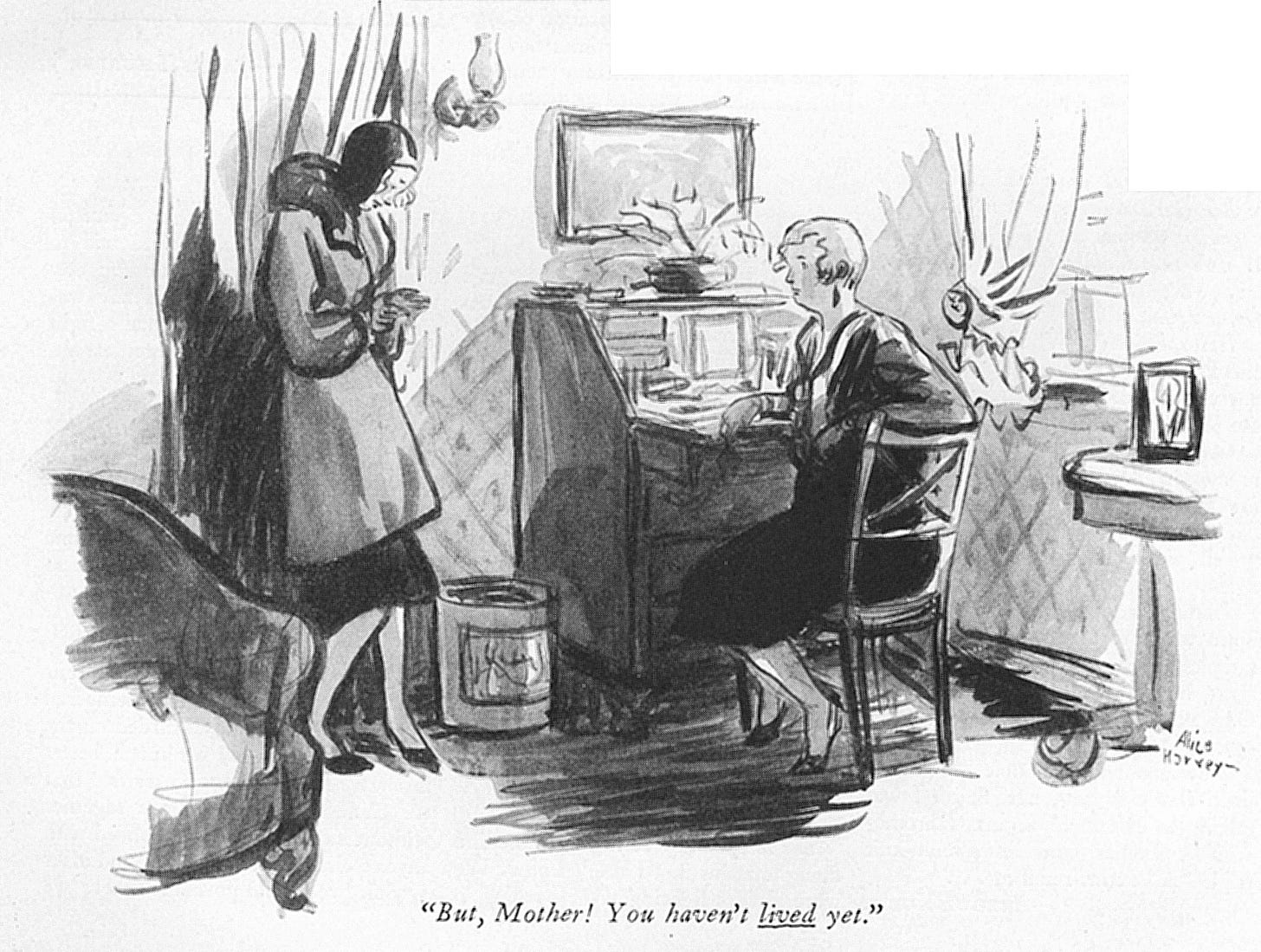

I don’t know what the drawing was that Harvey and Ross were debating. But just so you can see her work, here are two of Harvey’s drawings from The New Yorker around that time. She seemed like someone I would have loved to have known.